A Garden Club Committed to Civic Work

A Garden Club Committed to Civic Work

The history of the Cambridge Plant & Garden Club’s civic work goes back more than 100 years. From an early interest in playgrounds at the city’s settlement houses and children’s gardens, the club turned in the 1930s to planting trees and shrubs at the Cambridge Common. In the 1960s, members’ attention focused neglected landscapes at Fresh Pond Reservation as well as to garden restorations at two historic houses. Spurred by these projects, in 1979, two club members founded the Cambridge Committee on Public Planting to promote tree planting in the city’s parks, at schools, and along streets; forty-five years later, club members continue to be engaged in the committee’s leadership. The club is also proud that the Charles River Conservancy was founded by a member and that members were also early supporters of CitySprouts, a hands-on schoolyard gardening program.

With the increasing recognition of climate change, CP&GC has redoubled its advocacy for trees. A city’s tree canopy contributes not only shade and beauty, but can have an immediate impact on reducing heat island effects in a densely populated city like Cambridge. The club’s commitment is reflected in the fact that two CP&GC members served on the committee that produced the Cambridge Urban Forest Master Plan (published in 2019). Advocacy for trees, along with open space, is now at the heart of the club’s work.

Over the years, the CP&GC has funded tree planting and other improvements at public sites throughout Cambridge – Fresh Pond Reservation, Lowell Park, Longfellow Park, Magazine Beach, Blair Pond, Raymond Park, Garden Street Glen, Winthrop Park, Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge Common, Gold Star Mothers Park, Hell’s Half Acre (Greenough Boulevard), Craigie Street Park, various schools, and mostly recently Memorial Drive, where the club has made a major gift toward the replanting of the parkway’s allée of London Plane trees. At the same, the club has worked to enhance the plantings at a number of nonprofit organizations [should we list some of the organizations?]. Recently, the club has redoubled attention on small neighborhood parks, and also focused new attention of the city’s community gardens and the planting of pollinator gardens.

Over the years, the CP&GC has funded tree planting and other improvements at public sites throughout Cambridge – Fresh Pond Reservation, Lowell Park, Longfellow Park, Magazine Beach, Blair Pond, Raymond Park, Garden Street Glen, Winthrop Park, Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge Common, Gold Star Mothers Park, Hell’s Half Acre (Greenough Boulevard), Craigie Street Park, various schools, and mostly recently Memorial Drive, where the club has made a major gift toward the replanting of the parkway’s allée of London Plane trees. At the same, the club has worked to enhance the plantings at a number of nonprofit organizations [should we list some of the organizations?]. Recently, the club has redoubled attention on small neighborhood parks, and also focused new attention of the city’s community gardens and the planting of pollinator gardens.

CP&GC’s civic work is supported by the nonprofit fundraising and the hands-on commitment of members.

Read Centennial Time Line, 1889–1998 [PDF].

The Roots of CP&GC: The Plant Club

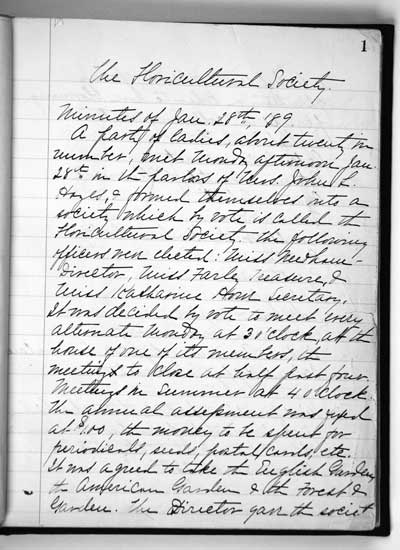

Talent and passion for plants joined together several Cambridge women in January 1889. They became the Floricultural Society, but at its second meeting this new club was renamed the Plant Club. Early conservationists, members supported the fledgling “Society for the Protection of Native Plants” now named the Native Plant Trust, the first conservation organization for plants in the United States.

Talent and passion for plants joined together several Cambridge women in January 1889. They became the Floricultural Society, but at its second meeting this new club was renamed the Plant Club. Early conservationists, members supported the fledgling “Society for the Protection of Native Plants” now named the Native Plant Trust, the first conservation organization for plants in the United States.

The rich academic community in which the Plant Club was founded created the template still followed by today’s members: educational presentations by scientists, historians, designers, conservationists and members alike that became the central feature of their meetings. Informal committee meetings enhanced the intellectual pursuits of members—sharing their own horticultural knowledge. Recipes for fertilizers and soil enrichment, pest treatments, garden walks and visits, and propagation best practices were among the expertise shared by members.

Interest in the Plant Club grew as its civic work expanded, however membership was quite limited. A sister club was founded in 1938 — the Cambridge Garden Club. Members of the new club, including several Plant Club women, were soon thrown into their first conservation project – helping in the cleanup and restoration after the Great Hurricane of 1938. The shared interests of both clubs led to many joint meetings, programs and outreach projects. Children’s gardening was a particular focus. A campaign in the late 1950s to save 36 acres of marshland along the Charles River from the four-lane Greenough Boulevard failed, but lessons learned set the stage for future successes.

Interest in the Plant Club grew as its civic work expanded, however membership was quite limited. A sister club was founded in 1938 — the Cambridge Garden Club. Members of the new club, including several Plant Club women, were soon thrown into their first conservation project – helping in the cleanup and restoration after the Great Hurricane of 1938. The shared interests of both clubs led to many joint meetings, programs and outreach projects. Children’s gardening was a particular focus. A campaign in the late 1950s to save 36 acres of marshland along the Charles River from the four-lane Greenough Boulevard failed, but lessons learned set the stage for future successes.

Early in the 1960s, the two clubs embarked on a large conservation project at Fresh Pond Reservation – the City’s largest open space. In partnership with the City, the clubs reclaimed and replanted Blacks Nook, a site that had come to be used for dumping. The experience galvanized members—as organizers, workers, and fundraisers—and the two clubs joined together create the Cambridge Plant & Garden Club. The newly combined organization applied for membership in national group The Garden Club of America, becoming a member in 1968.

Early in the 1960s, the two clubs embarked on a large conservation project at Fresh Pond Reservation – the City’s largest open space. In partnership with the City, the clubs reclaimed and replanted Blacks Nook, a site that had come to be used for dumping. The experience galvanized members—as organizers, workers, and fundraisers—and the two clubs joined together create the Cambridge Plant & Garden Club. The newly combined organization applied for membership in national group The Garden Club of America, becoming a member in 1968.

CP&GC turned its attention to the restoration of other green spaces in the city though Fresh Pond work continued. CP&GC launched a restoration of the Longfellow House garden and grounds and also focused its energy on the garden at the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House History Cambridge. A project that had begun as a Garden Club effort in 1961 continues today. Other planting projects have taken CP&GC to public schools, parks, and many green spaces and non-profits across the city.

The Plant Club’s founders would perhaps be astounded by the way their club has expanded, but they would have hoped for no less. CP&GC is proud that its archives reside at the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in the United States.

“What’s in a Name?” or “Is This the First Garden Club?”

“What’s in a Name?” or “Is This the First Garden Club?”

There is often controversy surrounding the honor of being first established – whether in the realm of schools, colleges, hospitals, or special-interest clubs. Garden clubs are no exception. The first women’s garden club was a Cambridge club – the Garden Street Garden Club, founded in 1879. After the Plant Club was founded in 1889, the Garden Street Garden Club gave way to the younger club. The third oldest women’s club was the Ladies’ Garden Club of Athens, Georgia, which held its first meeting in 1892. Around 1930, a controversy arose between the Cantabrigians and the Athenians concerning which of the two clubs was an older and truer garden club.

The dispute is laid out “What’s in a Name?’ or ‘Is This the First Garden Club?’” – written by CP&GC historian Annette LaMond and originally published by the Cambridge Historical Society (now History Cambridge). The paper includes a number of images drawn from the archives of the CP&GC. Read a PDF of the article here.

A History Reclaimed: The Society for the Protection of Native Plants and the Cambridge Plant Club

A History Reclaimed: The Society for the Protection of Native Plants and the Cambridge Plant Club

Members of the Cambridge Plant Club developed an interest in the conservation wild flowers in the 1890s, and became subscribers of the Society for the Protection of Native Plants soon after its founding in 1901. This paper by Annette LaMond gives a history of this early conservation organization, and its subsequent transformation into the New England Wild Flower Society. The paper, which includes many illustrations, also gives new recognition to the roles of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and The Garden Club of America in supporting the protection of native plants. Together, the two organizations encouraged a succession of ardent gardeners, including our club’s members, to dedicate their volunteer energy to the New England Wild Flower Society, paving the way for today’s vibrant Native Plant Trust. Read a PDF of the essay HERE.

Index to Plant Club Speakers, 1889–1965

Annette LaMond

This index of Plant Club speakers includes many names that are still known today, at least in their fields or by local historians. Quite a few were Harvard professors; one of the first to address the club was the Arnold Arboretum’s Charles Sprague Sargent. Notably, some of the professors specialized in other fields, such as classics and archeology, but were formidable botanists and horticulturists nonetheless. Among the landscape designers who spoke to the club were Mabel Babcock; Paul Frost; Warren Manning (who also provided advice on civic projects); and Fletcher Steele. (Babcock and Steele designed gardens for several club members.) Well-known botanists include Alice Eastwood; Margaret Clay Ferguson; Merritt L. Fernald; George L. Goodale; Paul C. Mangelsdorf; and Benjamin L. Robinson. Plantswomen and plantsmen who shared their knowledge include Mrs. Hugh Hencken (before she became television personality Thalassa Cruso); John George Jack; Kathryn Taylor; Helen Noyes Webster (better known as Mrs. Hollis Webster); and Donald Wyman. Quite a few speakers were conservationists. Although their names may no longer be familiar, they played lead roles in saving thousands of acres that are now beloved sanctuaries. Among them: Annette Cottrell; Walter Deane; Kay Kulmala; Winthrop Packard; and Theodore Lyman Storer. Other speakers – Emma G. Cummings; Kaneji Demoto; Robert T. Jackson; Edith H. Scamman – defy categorization and should also be better known. This is also true of member speakers. It is my hope that the history of the Plant Club, viewed through its programs, will give new recognition to all the speakers in this index.

A History in One Thousand Programs (More or Less): The Cambridge Plant Club, 1889–1965

Plant Club record book, Volume I, page 1. Originally the Floricultural Society, the simpler Plant Club moniker was adopted at the club’s second meet- ing on February 11, 1889.

Read about the Cambridge of the 1880s and the women who came together in the unseasonably warm winter of 1889 to found a garden club. The moniker “Garden Club” was not yet a term of art (or obvious choice), so they debated and settled on a simple name – Plant Club – which expressed their shared interest in growing plants well, indoors and out. This essay describes how members of the club were continually inspired and re-energized by expert speakers, including from their own ranks, and how over the years, a passion for gardening turned into advocacy for conservation and civic planting in Cambridge and beyond.

Sixty Years of Gardening at the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House

Sixty Years of Gardening at the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House

The Hooper-Lee-Nichols House was donated to the Cambridge Historical Society in 1957. After settling into the house, the Society reached out to the then separate Cambridge Garden Club (founded 1938) and Cambridge Plant Club (founded 1889) about the care of the grounds. The Garden Club, which was considering a project to celebrate its upcoming 25th anniversary, accepted the invitation as a major project.

Thanks to a 1920s renovation, the HLN garden had good bones. Garden Club members set to pruning existing plant material (including the crabapple trees that still grace the entrance). Out of this hands-on work came a collaborative design for a colonial-era estate in miniature. Features: yew hedges, lawns, roses, herb garden within a boxwood circle on the west of the house, and orchard to the east. To realize the plan, members propagated boxwood and yews. The club’s horticulturists accomplished a great deal on a surprisingly small budget.

At the project’s five-year mark, the club planted a little-leaf linden at the south- east corner, still a feature, and a fringe tree, which is not. The yews, which had grown vigorously, were spaced out to extend the hedge that endures as a sig- nature of the garden. Also honoring the club’s early work – an armillary sundial for the center of the boxwood circle – was donated by a club member after it made an appearance in a Massachusetts Horticultural Society spring flower show.